FREE shipping on orders of $200+

Quantity discounts and shipping details here.

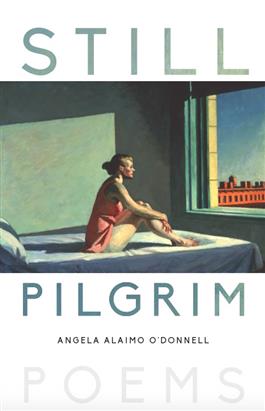

Paradox at the Heart of Poetry—In Review

August 4, 2017)

Paradox colors the world, especially when seen through the eyes of faith, and paradox is at the heart of these poems. Consider the collection’s title: Still Pilgrim. How can a pilgrim, who is a traveler by definition, be characterized as still? “This world was never made for rest,” says “The Still Pilgrim Ponders a Paradox,” the poem serving as the book’s epilogue. “And still you stay as still can be / unmoved by your velocity.”

In these poems, the Still Pilgrim—seemingly the poet’s alter ego—reflects on longing and the world’s impermanence, the fleetingness of time and vivid memories, piercing joy and piercing grief.

In these poems, the Still Pilgrim—seemingly the poet’s alter ego—reflects on longing and the world’s impermanence, the fleetingness of time and vivid memories, piercing joy and piercing grief.

“We are living in an anti-art age. The world is now a brutal place and obsessed with speed and wealth.” So said singer and songwriter Paul Simon in a 2015 interview, and one could understandably fear, in such an age as ours, that poetry has finally become irrelevant. But I would like to think, and Angela O’Donnell’s engaging and deeply humane poems in Still Pilgrim encourage me in doing so, that poems will go on functioning as diverse mercies we can keep with us—at home or away—for the pleasure of their company and as a means of remembering who we are.

Read the full review from The Christian Century

Angela Alaimo-O’Donnell on how Stil Pilgrim came to be…